According to the US National Institute of Standards and Technology’s (NIST) page on Combinatorial Testing, combinatorial testing can reduce costs for software testing, and its applications in software engineering can be significant. This is not surprising, as combinatorial testing is the cornerstone of any type of software testing. In its simplest form, one can think of it as finding the correct combination for a padlock. But instead of looking for a combination that opens the lock, the quality assurance team looks for combinations that lead to a violation of one or more requirements—the bugs. The technique is simple and universal, and in theory, it provides the most sought-out feature in testing, which is complete test coverage.

Combinatorial methods can reduce costs for software testing and have significant applications in software engineering.

What is combinatorial testing?

Combinatorial testing is a technique that checks all, the exhaustive case, or just some combinations of system inputs. The most common application of combinatorial testing is to check combinations of input parameters or configuration options. Checking combinations of the system’s input parameters is the simplest form of application. A system can either be complex or be as simple as a function.

Applying combinatorial testing

For example, here is a function that defines a pressure switch. This function has bugs for some specific combinations of values for the pressure and volume input parameters. Combinatorial testing would check the pressure switch function against all possible combinations of pressure and volume.

1 | def pressure_switch(pressure, volume): |

Let’s assume that the pressure parameter could take values {0, 10, 20, 30, 40},

and the volume parameter could have values {0, 50, 100, 150, 200, 250, 300}.

Given that the pressure has 5 possible values and the volume

has 7 possible values, the total number of all combinations is 35.

We can write a simple test scenario to check all of these combinations using a simple nested for-loop.

1 |

|

In general, the total number of combinations, , is simply the product of number of values for each parameter.

The complete  test program would be the following:

test program would be the following:

1 | from testflows.core import * |

Executing the program above would produce the following output:

1 | Oct 10,2023 16:38:44 ⟥ Scenario check pressure switch |

Computing combinations using the Cartesian product

A simple nested for-loop solution only works well when the number of combination variables is small. However, it does not scale if the number of parameters is large. In this case, using a Cartesian product function comes in handy.

The Python standard library provides itertools.product function that calculates the Cartesian product of iterables, and we can use it to remove nested for-loops. The testflows.combinatorics module conveniently provides it.

itertools.product(*iterables, repeat=1)

Cartesian product of input iterables.

Using the product function, we can rewrite the scenario to check all input parameter combinations

of the pressure switch function as follows:

1 | from testflows.combinatorics import product |

As we can see, now we have only one for-loop instead of two, and if the number of combination variables was greater than two, then we would not need to add any more nested loops but instead would just pass more variables into the Cartesian product function.

Exhaustive testing and the combinatorial explosion problem

Even though we could pass as many iterables as we want into the Cartesian product function, one for each of our input parameters, the number of combinations will quickly grow, and exhaustive testing would become infeasible due to the combinatorial explosion problem.

The combinatorial explosion arises from the fact that the total number of combinations, , grows very rapidly, exponentially, as the number of parameters increases and becomes even worse when the number of values for each parameter is large.

For example, if we have 10 parameters (n = 10) that each have 10 possible values (v = 10), the

number of all combinations is , thus requiring 10 billion

test combinations for complete test coverage.

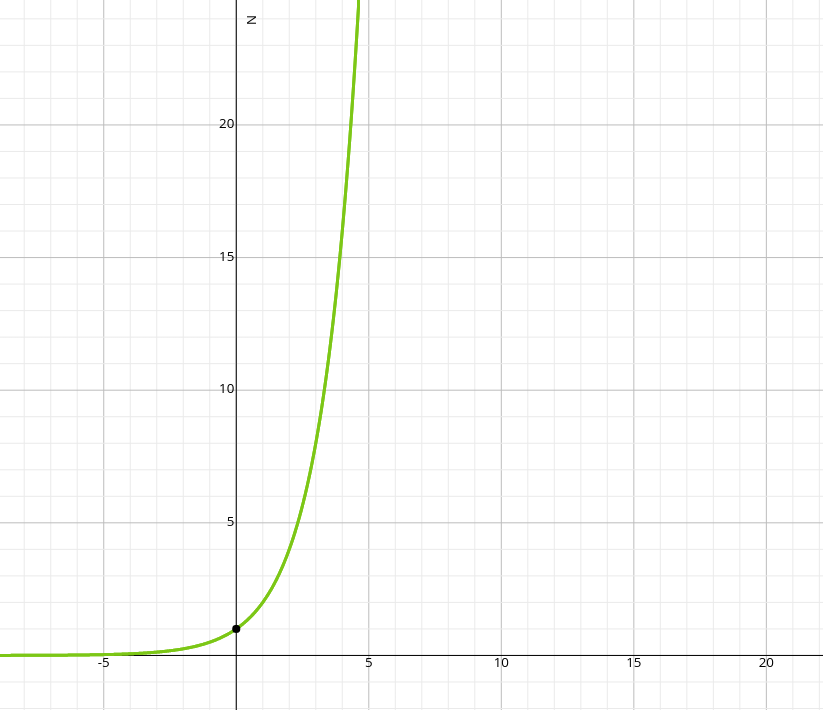

If we take the case where each parameter has the same number of values, then we will get:

If we graph this formula for the case, with the x-axis being the number of parameters, , and the y-axis being the number of combinations, , then it will look as follows:

To make it even worse, the line gets even steeper as we increase the value of !

So, can we conclude that combinatorial testing is a lost cause? Actually, not really, and far from it! However, this is a topic for another blog article. So please stay tuned.

If we take the case where each parameter has the same number of values, then we will get that .

Conclusion

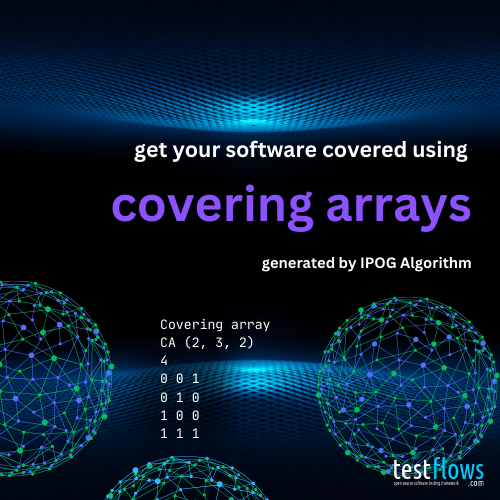

This was a brief introduction to combinatorial testing. We’ve seen a simple example of applying the combinatorial testing technique to a simple pressure switch function and explored two solutions that checked all possible combinations of its input parameters. The first naive solution using a nested for-loop suffered from scalability issues if the number of combination variables increased. The second solution using the Cartesian product function solved the scalability issue but still ran into problems with combinatorial explosion when the number of input parameters in the system increased and exhaustive testing of all possible combinations became infeasible. Nonetheless, the principles of combinatorial testing were applied successfully. Working around the combinatorial explosion problem is not trivial, but techniques such as using covering arrays can help us make combinatorial testing practical.

If you want to know more, read our introductory article on covering arrays titled Get Your Software Covered Using Covering Arrays.

For more in-depth overview of combinatorial testing, please read an excellent article provided by NIST titled Practical Combinatorial Testing. Also, read the Combinatorial Tests section in the Handbook to find out more about how  supports combinatorial tests.

supports combinatorial tests.