Combinatorial testing significantly increases the test coverage of software systems, achieving levels of thoroughness that are unattainable with traditional test suites focusing on individual scenarios or limited combinations of user actions. However, combinatorial testing introduces the notorious test oracle problem—how to determine or compute the expected behavior for every possible combination of user actions.

The survey “The Oracle Problem in Software Testing: A Survey” provides an excellent overview of this issue, highlighting that deriving or even knowing the correct outcomes for complex combinations is often not straightforward. A common approach to solve this is by developing a behavior model that can compute expected outcomes for given system behaviors. Yet, many testers have never encountered the oracle problem, as they primarily deal with single combination tests. Fewer still have created or even understand what a behavior model entails.

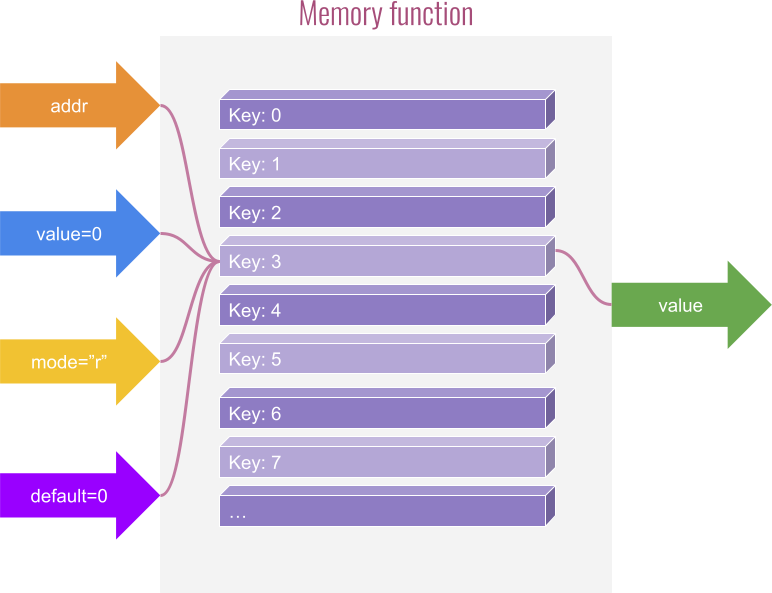

To demystify behavior models, we will explore the development of such a model for a simple stateful system: a memory function that allows users to write, read, or erase data. We’ll illustrate how to apply combinatorial testing to this function and develop a behavior model from scratch to verify expected results.

The memory function

To illustrate the approach, we’ll use a memory function as our system under test. This system is straightforward to understand, yet the technique is easily adaptable to more complex, real-world systems.

In Python, we’ll define the memory function as follows:

1 | def memory(addr, value=0, mode="r", default=0, mem_={}): |

Understanding the memory function

The memory function allows users to write or read values at specific addresses and erase all memory contents. Memory is managed by the mem_ dictionary, which retains its contents between function calls. The default argument defines the value returned when no value has previously been stored at the specified address.

The mode argument controls the operation performed by the memory function and can include any combination of the following flags:

'r'- Read a value from the specified address.'w'- Write a value to the specified address.'e'- Erase all memory contents.

The function only raises exceptions if the addr is a non-hashable value, resulting in a TypeError, since dictionary keys must be hashable.

When multiple mode flags are set (e.g., 'rwe'), the operations are performed in a specific order: read first, then erase, and finally write. Since the memory function represents a stateful system, the sequence of user actions affects the results, making the order of actions important.

For example, attempting to read from a memory address before writing to it will return the default value, while writing first allows the correct value to be read later.

Defining user actions

Whether or not one uses combinatorial testing techniques, explicitly defining all possible user actions is crucial for effectively testing any system.

What are the possible user actions for the memory function? Here is the complete list:

- The user can call the

memoryfunction with specific arguments. - The user can expect to receive a default value.

- The user can expect to receive a stored value.

- The user can expect to encounter an error, such as a

TypeErrorexception when theaddris non-hashable.

The last three actions can generally be categorized as “checking the result.” However, the action of “checking the result” is too generic. To thoroughly test the correct behavior of the memory function, each expectation must be explicitly identified.

Note that we have kept the action of calling the memory function generic, rather than breaking it into separate actions based on specific combinations of arguments. This is because we aim to explore as many argument combinations as possible during testing.

Below is the definition of these actions in code, where each action is represented as a test step:

1 |

|

It is important to note that the library of user actions can be built incrementally. This approach is crucial for real-world systems, where the complete list of user actions may not be clear at the project’s outset. However, it is also important to recognize that failing to identify possible user actions will inevitably result in gaps in test coverage.

Writing a combinatorial test

With the user action steps defined, we could write a number of simple tests to start verifying different functionalities. However, how many tests do we really need? Many testers don’t even consider this question, and after writing ten, twenty, or perhaps hundred tests, they often assume that is sufficient.

To determine how many tests are truly needed, we first have to calculate the number of ways a user can call the memory function. Next, we need to consider the length of the sequence of calls that users can make and determine the minimum sequence length before we start seeing repeated behaviors in the system.

To calculate the number of ways a user can call the memory function, we need to identify all possible values for each argument that the memory function accepts and multiply these possibilities together.

Specifically, we need to know all possible values for:

addrvaluemodedefault

The number of possible valid values for the addr, value, and default arguments is effectively unlimited from a practical perspective because:

addrcan be any hashable object.valuecan be any object.defaultcan be any object.

On the other hand, the number of possible valid values for the mode argument can be calculated as follows:

1 | from testflows.combinatorics import combinations |

This results in the following list of possible mode values:

1 | ['r', 'w', 'e', 'rw', 're', 'we', 'rwe'] |

This list is derived from , where represents the number of ways to choose unordered elements from elements. In our case, is , corresponding to the valid flags (r, w, e), and we are choosing up to elements.

The calculation can be done using the combinations function from Python’s itertools standard module, or alternatively, you can import it from the testflows.combinatorics module for convenience.

The number of possible valid values for the mode argument is 7, resulting in the following possible values for each argument:

addr: Any hashable object.value: Any object.mode: One of possible values ('r','w','e','rw','re','we','rwe').default: Any object.

There are also numerous invalid mode values or values that are partially valid, such as the string 'write me a letter', which would be treated as 'rwe' due to containing all the valid flags. However, for simplicity, we will focus only on the valid values.

Handling infinite combinations with representative values

How do we handle the fact that the number of ways a user can call the memory function is practically unlimited? The solution is to select “representative” valid values.

A “representative” value can be informally defined as a value that will produce the same behavior as other values sharing the same characteristics. For example, we can use the number 1000 as a representative value for addr, assuming that other integers used as addr will behave similarly. Furthermore, since 1000 is hashable, we can assume that other hashable objects will behave the same way.

A formal definition connects the concept of a “representative” value to equivalence classes as follows:

A representative value is an element within a set that belongs to an equivalence class under a defined equivalence relation , such that for any other element , the behavior of a function or system when applied to is equivalent to its behavior when applied to . This means for all , where denotes behavioral equivalence.

Of course, these assumptions may or may not hold true. We could even test these assumptions by keeping all other arguments fixed while iterating over different values for a given argument assumed to belong to the same representation class. However, the number of representation classes depends on the number of potential failure modes, which we might not know in advance. Therefore, choosing the “right” representative values is not trivial, but we can start with some reasonable choices.

For example, we can select the following values:

addr: Either1000or2000.value: Either'hello'or'hello2'.mode: Any of the 7 valid modes ('r','w','e','rw','re','we','rwe').default: Either0orNone.

Using these representative values, we can write a combinatorial test to explore all possible ways to execute the memory function. Additionally, we will go further and check all possible sequences of such calls, up to a specified number_of_calls.

Sketching the test

Sketching such combinatorial tests using  is straightforward. We can use the TestSketch decorator along with the either() function as shown below:

is straightforward. We can use the TestSketch decorator along with the either() function as shown below:

1 |

|

The test code above checks up to number_of_calls sequential memory calls, covering all possible ways to call the memory function each time. In this case, there are possible ways to call the memory function based on our chosen values.

First test program

Below is the first version of the test program that we can execute:

1 | from testflows.core import * |

First test program output

When executed, this test program produces the following output:

1 | Passing |

The output indicates that all combinations were successfully executed without any failures.

The detailed test log for the first combination is below:

1 | Oct 07,2024 13:30:11 ⟥ Combination pattern #0 |

In this output:

- Combination pattern #0 represents the first of the test combinations.

- The test starts by erasing the memory to ensure a clean state before proceeding.

- It then executes the memory call

memory(addr=1000, value=hello, mode=r, default=0)and confirms the result is(0, None)— meaning the default value of 0 is returned, and no exception occurs.

The full log illustrates how each combination is executed in sequence, and provides a clear view of the memory operations and their outcomes. By exploring all combinations, we ensure comprehensive coverage of different input scenarios for the memory function using our selected representative values.

Increasing number of calls

To demonstrate how easy it is to extend our test program, we can increase the number of memory function calls to by modifying the feature that calls the check_memory combinatorial sketch and passing number_of_calls=2:

1 |

|

By executing this modified test program, we will observe that it now results in combinations being covered! This is calculated as combinations for the first memory call multiplied by combinations for the second memory call, giving us a total of:

combinations

1 | Passing |

This output demonstrates that increasing the number of sequential memory calls results in an exponential increase in the number of combinations covered, ensuring even more comprehensive test coverage. In this case, the test program executed different combinations giving us greater confidence in the correctness of the memory function for longer sequences of calls.

Determining the minimum number of calls

We have seen how easily we can adjust the length of the sequence of memory function calls. Now, it would be beneficial to determine the minimum number of calls needed to ensure comprehensive coverage of all possible system states.

To simplify our analysis, let’s consider a simplified model of the memory function with the following assumptions:

- All addresses are considered identical (indistinct).

- The specific values stored are irrelevant.

- Overwriting previously stored values is significant.

With these assumptions, we can represent the system in terms of abstract states—broad states that summarize the underlying conditions of the system. The simplified system can exist in only three distinct abstract states:

- State 0 (Uninitialized): No write operations have been performed.

- State 1 (Initialized without Overwrites): At least one write operation has been performed to an uninitialized address, but no overwrites have occurred.

- State 2 (Initialized with Overwrites): At least one overwrite operation has occurred (i.e., writing to an address that has already been written to).

Mathematically, we represent the set of possible system abstract states as:

where each corresponds to one of the abstract states above.

By applying the Pigeonhole Principle—which states that if items are placed into containers, and , then at least one container must contain more than one item—we conclude that after operations (the number of unique abstract states ), any subsequent operation () must result in an abstract state that has already occurred, causing a repetition. Formally, since , an abstract state must repeat.

Thus, the minimum number of operations before the system abstract state repeats is:

This understanding is crucial for effective testing and allows us to ensure that all possible combinations of representative values are tested using the fewest necessary operations. By ensuring that the number of operations , we guarantee comprehensive coverage of all system abstract states, facilitating thorough verification and validation of the memory function’s behavior.

The analysis shows that we need to set number_of_calls to 3

and the total number of combinations using our chosen values is:

Introducing the behavior model

So far, our combinatorial test sketch was actually a dummy and did not check the returned value and exception after calling the call_memory action. To fix that, we need to write a behavior model that can calculate the expected result and exception for any possible combination of memory calls.

Conceptually, the behavior model needs to implement only the expect method, which takes the current behavior (i.e., the current sequence of states) and returns a function that takes the current result and exception and asserts if they are correct. The model’s expect method should just contain an or expression that will select the expected user action with predefined values (using partial functions).

To implement the behavior model, we need to define two key classes: State and Model.

The State class

The State class must represent the state of the system at a given point in time and

is defined as follows:

1 | class State: |

Each State object captures the relevant parameters of a memory operation, including the address (addr), value (value), mode (mode), default value (default), and any error (error). These state objects are used to represent the sequence of operations that have been performed, forming the current system behavior.

Notably, the state does not include the output value directly, as it is computed by the model. It captures all input variables (addr, value, mode, default) and one output variable (error). While the error variable could be excluded to maintain purity and focus solely on inputs, including it simplifies the model’s logic. It allows easier computation of the expected result in the expect_stored_value method, which will be implemented in the model’s class. Therefore, it’s part of the state representation.

For more complex systems, the State class could include all input and output variables. However, extra care must be taken when computing the expected result of the system’s behavior to avoid improperly using the actual output in the calculation, as this could mask potential errors. Therefore, when practical, restricting the State attributes to only inputs acts as a safeguard against such mistakes, ensuring the integrity of the behavior model.

The Model class

The Model class implements the behavior model of the memory function. Its primary responsibility is to determine the expected outcome of each memory operation based on the sequence of states, which defines the system’s behavior. The class includes methods that analyze this behavior to predict the correct outcome in the current state, which is always the last state in the sequence.

expect_errorMethod: This is method checks if an error is expected based on the current state. For example, if the address is not hashable (e.g., a list), this method will predict that an error should be raised.expect_default_valueMethod: This method returns the default value if no write operation has modified the value at the specified address. It helps determine the expected output when a read operation is performed on an uninitialized memory address.expect_stored_valueMethod: This method checks if a previously stored value should be returned. It considers the impact of previous write operations and whether there have been any erase operations that would have cleared the memory.expectMethod: This is the main method of the model which calculates the correct expectation by invoking one of the above methods, based on the current behavior. It uses anorexpression to select the first valid expected outcome.

The Model class is defined as follows:

1 | class Model: |

The expect method

The expect_error is the main method and the order of methods in the or expression defined within this method is important:

1 | def expect(self, behavior): |

expect_error: The model first checks if an error should be expected for the current state, such as when an address is unhashable.expect_stored_value: If no error is expected, the model then checks if a stored value should be returned based on prior operations.expect_default_value: If no error or stored value applies, the model defaults to expecting the predefined default value.

The or expression ensures that the first applicable outcome is returned, which makes the model efficient and deterministic.

Note that there is a clear distinction between the model’s expect methods and the user actions that take place during testing:

The model’s expect_* methods predict what should happen based on the sequence of operations. The corresponding user actions (test steps) are then used to verify that the actual behavior of the memory function matches the predicted behavior.

For example, the model’s expect_stored_value method returns a partial expect_stored_value user action, which will be called later in the check_result action to assert that the observed behavior matches the expected behavior.

It’s important to note that the expect method is built iteratively as you model the system’s actual behavior and check if it aligns with the desired behavior. For instance, the first version of the expect method could be as simple as the following, where we initially expect only the default value to be returned for any behavior:

1 | # the first incorrect version |

This initial implementation is obviously incorrect but serves as a stepping stone in the model’s development. Running tests will reveal failing combinations where this expectation is invalid. If all combinations pass, it indicates a mistake in the test code, as we expect some combinations to return a stored value and others to return the default value.

The expect_default_value method

Since the expect_default_value method is called last in the expect method, it is the simplest to implement. This is because it serves as the default expectation. It becomes the default because it is the final part of the or expression, meaning that if no other expectations are met, the model will return its result as the default expectation.

1 | def expect_default_value(self, behavior): |

The method just needs to retrieve the current state, which is the last element in the behavior list, and return a partial expect_default_value action where the default value is set to the current_state.default value — where current_state.default is the default value passed by the user in the last memory function call.

The expect_error method

The next method in terms of complexity is the expect_error method. This method implements

the behavior where we expect an error only if the addr value is unhashable.

1 | def expect_error(self, behavior): |

To determine if an error should be expected, we only need to examine the current state, which is the last element in the behavior list. This list stores the sequence of states that fully describes the system’s behavior at this point.

We know that an error should only be returned if we are trying to write or read, which means checking for the presence of the w or r flags in the mode attribute of the current state. If neither flag is present, the method should just return, which effectively means returning None. This results in a False value in a boolean context, allowing the or expression inside the expect method to check the next expectation.

We then check if the addr value is hashable by attempting to get a hash using the hash function. If an exception is raised, we return a partial expect_error action with the error argument set to the raised exception.

The expect_stored_value method

The most complex expectation method is expect_stored_value. This method computes the expected value stored at the given addr, accounting for operations such as uninitialized values, memory erasure, and overwrites. To achieve this, it iterates through all states except the current one in the behavior sequence.

A more efficient implementation could start from the state immediately before the current one and move backward, which would be optimal for longer sequences. However, since the behavior list is expected to be short, we prioritize intuitive logic over premature optimization.

1 | def expect_stored_value(self, behavior): |

The current state, default value, and expected stored value are set, where the default stored value is simply the default value for the current state. This logic is managed by the initial lines:

1 | current_state = behavior[-1] |

Next, we short-circuit and return None if we are not reading the memory in the current state. There’s no need to compute a stored value if no read operation is occurring:

1 | if not "r" in current_state.mode: |

If we are reading, we loop through each state in the behavior, except for the current state, to determine what the stored value should be:

1 | for state in behavior[:-1]: |

Inside the loop, we handle two cases: when memory is erased and when a new value is written to the address.

Memory Erasure: If the e flag is set and no error occurs during a read operation, the memory is considered erased, and we set the stored value to the default value. This ensures that failed reads (with both r and e flags) don’t overwrite memory erasure.

Memory Write: If a write (w) occurs at the same address without error, we set the stored value to the value written in that state. If both r and w flags are set, reading is prioritized, and we check for a failing read via the error attribute.

1 | if stored_value != default_value: |

Finally, after iterating through the previous states, if the stored value differs from the default, we return a partial expect_stored_value action with the computed stored value. Otherwise, we return None and let the expect method proceed to check the next expectation.

Using the model in the test

Here is the modified version of the test that now uses the behavior model defined above. This version integrates the behavior model to automatically determine the expected results of each memory operation:

1 |

|

The check_result function is defined as a test step to validate the result of the memory function call. It takes several parameters:

r: The result of the memory operation.exc: The exception that was raised during the memory operation, if any.behavior: A list that stores the sequence of states representing the history of operations.model: The behavior model used to determine the expected outcome.

The function uses the behavior model to get the expect function, which will then be called to assert if the result (r) and the exception (exc) are correct.

1 |

|

Complete test program

Below is the complete test program that uses the behavior model, which we can execute to validate the behavior of the memory function, checking if the results match the expected behavior for any given sequence of operations:

1 | from testflows.core import * |

Complete test program output

When executed, the complete test program produces the following output:

1 | Passing |

This output shows that we executed combinations, covering all possible ways to execute a sequence of 3 memory function calls. Each combination is verified against the expected behavior as defined by the behavior model.

As an example, the detailed test log for the combination is shown below:

1 | Oct 07,2024 17:30:44 ⟥ Combination pattern #189 |

The log shows that we called the memory function times as specified by the number_of_calls argument:

- First Memory Call:

- The call attempts to read from the memory (

mode=r). - Since no previous value has been written to the specified address (

addr=1000), the default value (0) is returned. - The behavior model correctly computed the expected outcome as

expect_default_value.

- Second Memory Call:

- The call writes the value

"hello"to the memory at address1000(mode=w). - The expected outcome was to write successfully without an exception, resulting in (None, None).

- The behavior model correctly computed

expect_default_valuesince it was a write operation without a read.

- Third Memory Call:

- The call reads from and writes to memory in one operation (

mode=rw). The value"hello2"is written, but it also reads from the memory address. - The previously stored value

"hello"(written during the second call) is returned. - The behavior model correctly computed the outcome as

expect_stored_value, indicating that the value stored earlier should be returned.

The log messages show debug information that provides insight into the behavior model’s expectations for each call. Entries such as [debug] expect=expect_default_value, r=0, exc=None indicate the expected outcome calculated by the model (expect_default_value) and confirm that the actual result (r=0) and exception (exc=None) match the expected result.

The output confirms that the behavior model accurately predicted the expected results for all 3 memory operations in this combination. The model’s predictions align perfectly with the actual outcomes, as evidenced by the OK status for each test step.

By executing 175616 combinations, we thoroughly validated the memory function across a wide range of input sequences, ensuring that all possible behaviors are correctly handled. This approach provides comprehensive coverage and confidence in the correctness of the implementation.

Conclusion

Combinatorial testing is a powerful method for exhaustively verifying the behavior of systems. By building a behavior model, we addressed the “oracle problem”—the challenge of determining correct outcomes for every possible combination of inputs. By focusing on representative values and abstract states, we were able to reduce the number of combinations and limit the maximum length of memory function calls, while still ensuring comprehensive coverage of the system’s behavior.

The behavior model, designed to compute the correct outcomes for a sequence of operations, was invaluable for testing a stateful system like the memory function. It allowed us to verify the correct behavior for combinations of three consecutive memory function calls. Although demonstrated with a simple system, this approach is scalable and adaptable to far more complex, real-world scenarios.

Ultimately, the combination of combinatorial testing and behavior models provides an efficient and systematic way to verify stateful systems, offering a level of test coverage and thoroughness that surpasses and can’t be achieved using traditional methods.