In software testing, you often hear terms like “condition,” “proposition,” “predicate,” “property,” and “invariant”—but what do they really mean? In this article, we’ll break each of them down by defining them in relation to the states and state transitions that make up state machines. After all, software programs are, at their core, state machines. To aid understanding, we’ll use a well-known puzzle: the Die Hard water jug problem as our reference system. To understand these terms, we will first define what a state is, what a sequence of states is, and how a system can be represented as a mathematical formula. As a bonus, we’ll also define what an assertion means.

The Die Hard Water Jug Problem

In the movie Die Hard with a Vengeance (1995), the characters face a logical challenge to defuse a bomb: measure exactly 4 gallons of water using only a 5-gallon jug and a 3-gallon jug, with access to an unlimited water source. This example was popularized by the TLA+ Video Course, and you can watch the scene on YouTube.

The problem can be represented as a simple state machine. Since we aim to define our terms precisely, we must first establish how these terms apply to states—and the Die Hard water jug problem will serve as our framework. In doing so, we will also define what a state is, what a sequence of states is, and how a system can be represented as a mathematical formula.

Water Jug Problem possible actions

To solve the problem, the trick is to use a sequence of available actions to achieve the goal. The possible actions and the resulting states are:

| Action | State (after action) |

|---|---|

| Fill the 3-gallon jug | |

| Fill the 5-gallon jug | |

| Empty the 3-gallon jug | |

| Empty the 5-gallon jug | |

| Pour from the 5-gallon jug into the 3-gallon jug | |

| Pour from the 3-gallon jug into the 5-gallon jug |

The initial state is .

Water Jug Problem state diagram

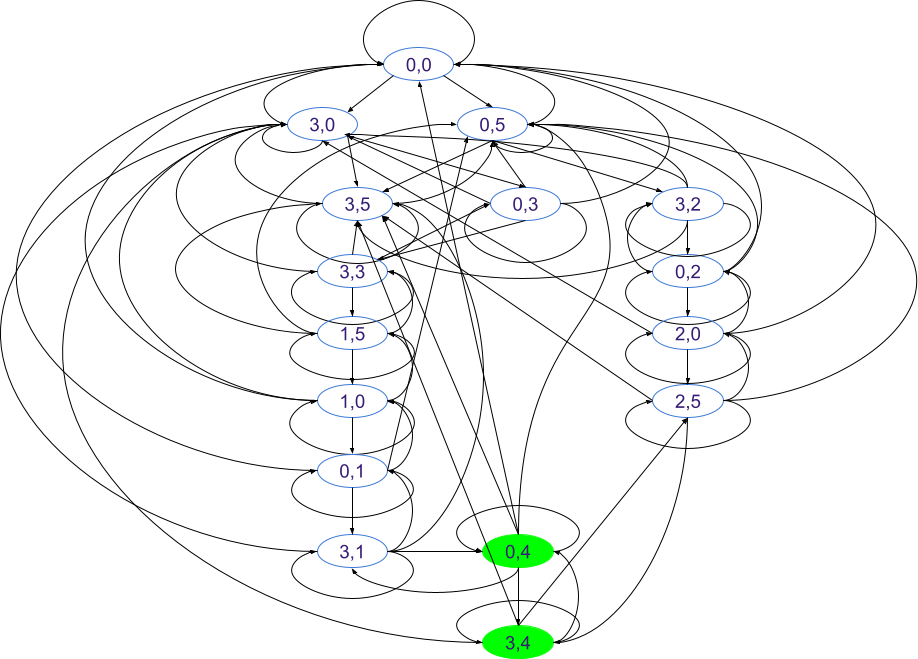

To help us understand states better we can visualize the “Die Hard water jug problem” using the following state diagram that shows all the reachable states and all possible state transitions:

The Die Hard Water Jug Problem: State Diagram

As we can see, the state diagram becomes quite complex, since at each state the user can execute one of six possible actions, each resulting in different state transitions. Furthermore, the graphical representation of state machines using state diagrams can quickly become messy, even for relatively small systems. Therefore, we will show that mathematics can help us describe this problem in a much more concise and elegant way.

All possible states (small, big)

| (0,0) | (1,0) | (2,0) | (3,0) |

| (0,1) | (3,1) | ||

| (0,2) | (3,2) | ||

| (0,3) | (3,3) | ||

| (0,4) | (3,4) | ||

| (0,5) | (1,5) | (2,5) | (3,5) |

Nonetheless, the state diagram shows that there are possible states. Why? Because we have possible values for the small jug () and possible values for the big jug (), giving us . However, only of these states are reachable. The states (1,1), (2,1), (1,2), (2,2), (1,3), (2,3), (1,4), (2,4) are not reachable, no matter what sequence of actions we perform. Nonetheless, we can see that using these two jugs, we can measure 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 gallons of water.

What’s a state?

A state is defined as assignment of values to variables and this means that any state is defined by its variables and the values that those variables have.

A state is an assignment of values to variables.

Therefore, for any system there are only two questions you really need to ask:

- What are the variables that define the state of the system?

- What possible values each state variable can have?

A state in the Die Hard water jug problem is simply a snapshot of how much water is in each jug at a given moment. We can represent a state as a pair , where:

- is a variable that defines the amount of water in the 3-gallon jug.

- is a variable that defines the amount of water in the 5-gallon jug.

Initial State: Both jugs are empty: .

Goal State: The 5-gallon jug contains exactly 4 gallons: , where can be any integer value from 0 to 3.

We, can also write the initial state using matrix-like notation:

Then, the only two solution states for the problem can be written as:

Let’s highlight the variables (they are in ):

Let’s highlight the values (they are in ):

Do you see that each state is indeed an assignment of values to variables and nothing else!

This principle is universal—it applies to any system and, therefore, to every program you will ever test. Programs have states, and these states are composed of variables that hold specific values. In essence, each state is defined by the unique combination of values assigned to its variables.

You can always add more variables

There is one more important aspect to understand about states. No matter what you think the state variables are for a given problem, you can always add more. In fact, there are infinitely many variables you could list to represent any given state. Of course, for simplicity we’ll try to keep the variable count to a minimum, but it’s essential to remember that a state might include additional variables beyond those we choose to focus on.

No matter what you think the state variables are for a given problem, you can always add more.

In our case, it’s convenient to think of the state as:

but more generally, you should think of the state as:

This generalization will come in handy later when we discuss how a property and an invariant can act as a condition.

What’s a sequence of states?

Knowing exactly what a state is helps us clearly understand what a sequence of states is—essentially, it’s just a series of states.

For example, one solution to the Die Hard water jug problem is the following sequence:

Each specific sequence of states defines a behavior.

What’s an action?

In the Die Hard water jug problem, we observed that there are six unique actions you can perform to solve the challenge.

Filling a Jug: Pouring water in until it’s full.

- Fill the 5-gallon jug

- Fill the 3-gallon jug

Emptying a Jug: Dumping all the water out.

- Empty the 5-gallon jug

- Empty the 3-gallon jug

Pouring Water from One Jug to Another: Transfer water until the source is empty or the destination is full.

- Pour from 5-gallon into 3-gallon

- Pour from 3-gallon into 5-gallon

However, what exactly is an action?

It turns out the answer is simple: an action is the act of assigning values to state variables.

An action is the act of assigning values to state variables.

For example, consider the Fill the 5-gallon jug action. In this case, the action assigns 5 to the variable and carries over the current value of to the next state as .

We can write this as:

Sometimes, you’ll read or hear someone define an action as

an operation that transitions the system from one state to another

This definition can be confusing because it might lead you to think that a transition always results in a different state. However, that’s not always the case. For example, starting from the initial state , performing the Fill the 5-gallon jug action gives you the next state . But if you perform the Fill the 5-gallon jug action again, the system remains in the state—no change occurs!

Even though the state doesn’t change, a new state is still added to the sequence of states. In other words, the system transitions in the sense that each action results in a new state being recorded, even if that new state is identical to the previous one.

A subtle but crucial difference to catch and understand!

State transition formula

The last thing we need to understand is that a program—just like any state machine—can be described using a mathematical formula. You might ask, “Why would I ever want to do that?” The answer is simple: as we’ve seen with the Die Hard Water Jug Problem, the state diagram can be extremely complex and hard to follow. Mathematics offers a much more elegant and concise way to express these transitions, as shown below:

Where we’ve added the input variable to help select the action to be performed. While the formula might look intimidating at first, don’t be worried—the represents a logical AND operation, and represents a logical OR operation. Also, note that since this is a mathematical formula, is the equality operator, not an assignment.

Just because a formula representaion might be more concise, why do we need it to define condition, proposition, predicate, property, and invariant? In short, without a precise mathematical representation of the system, these terms would remain abstract. By expressing the system as a collection of states, actions, and transitions in a formula, we can pinpoint exactly where and how each concept applies.

Defining the terms precisely

Having laid the foundation with our Die Hard water jug problem example, we are now ready to define precisely the terms condition, proposition, predicate, property, and invariant in terms of how they apply to states.

What’s a condition?

A condition is a boolean expression that serves as a guard for a state transition. It is the simple yes/no question (that’s why it is boolean) that determines whether a particular action (act of assinging values to state variables) is applicable in the current state.

A condition is a boolean expression that serves as a guard for a state transition.

For example, in the state transition rule for filling the small jug:

the condition is:

This condition answers the question: “Is the chosen action ‘fill_small’?” If it evaluates to true, the corresponding state transition occurs; if it evaluates to false, the transition does not take place.

What’s a proposition

A proposition is a statement that has a definite truth value—either true or false (boolean)—in a given state. A proposition makes a concrete assertion about the state of the system.

A proposition is a statement that has a definite truth value—either true or false (boolean)—in a given state. It makes a concrete assertion about the state of the system.

For example, in the Die Hard water jug problem, the statement:

is a proposition. It asserts that “the big jug contains exactly 4 gallons” and is either true or false in any particular state.

But wait, what about ?

Both and depend on state variables, but the key difference lies in how they are used and interpreted in context.

is typically treated as a proposition because it asserts a specific fact about the state (namely, that the big jug contains exactly 4 gallons). When evaluated in any given state, this statement is either true or false.

is used as a condition in the transition system. Although it also depends on the variable action, it functions as a guard that determines whether a particular state transition is triggered. It is a Boolean expression that tells us if the specified action is being applied.

In summary, while both depend on state variables, is considered a proposition (a fact about the state), whereas serves as a condition (a guard for a transition) in our system.

What’s a predicate?

A predicate is a logical formula that includes one or more free variables and evaluates to true or false once those variables are assigned specific values. It can be seen as a function from a domain (such as the states of a system) to Boolean values.

Consider the fill_big transition:

This is predicate because it has free variables:

- and : These represent the values in the current state.

- and : These represent the values in the next state.

- : This is also a free variable. Although the predicate includes the clause which restricts the value of to "fill_big" for this transition, remains a free variable in the formula—it receives its specific value when the predicate is evaluated in a particular context.

In contrast, a proposition is a declarative statement that is unambiguously either true or false in a given context—it contains no free variables. Once all variables are instantiated, a predicate becomes a proposition.

Comparison:

Predicate:

- Contains free variables.

- Its truth value depends on the assignment of those variables.

- Example: is a predicate because its truth depends on the value of action.

Proposition:

- Contains no free variables.

- Has a fixed truth value in any specific state.

- Example: If in a given state holds, then the statement “big = 4” is a proposition that evaluates to true.

In short, a predicate becomes a proposition once all its variables are assigned, turning it into a definite statement with a truth value.

So, is a predicate or proposition?

The expression is a Boolean expression that depends on the free variable .

- As a predicate: When is not given a specific value, the expression is a predicate because it can be seen as a function that takes as input and returns a Boolean value.

- As a proposition: Once is assigned a specific value, the expression becomes a proposition—it then has a definite truth value (either true or false).

Thus, in its general form with free, is a predicate. When the variable is instantiated with a specific value, it becomes a proposition.

But, is also a condition?

That’s right. A condition is expressed as a predicate—a Boolean expression with free variables that evaluates to true or false depending on those variable assignments. Thus, in our system, a condition—such as —is fundamentally a predicate. When all free variables are instantiated, it becomes a proposition.

What’s a property?

A property is a statement that is either true or false in a set of states or the behavior (sequence of states) of the system as it evolves over time. It is typically a predicate that is meant to hold over multiple states or even throughout an entire execution (for example, along every possible execution path). For instance, consider the property:

This property asserts that every state of the system must satisfy the jug capacities. It is not limited to a single state but is expected to hold across all (or a significant collection of) states of the system.

How does it compare to proposition?

A proposition, on the other hand, is a statement that makes an assertion about a single state—it has a definite truth value (true or false) in that state. Therefore,

- A proposition is a statement about one specific state.

- A property is a condition or rule that applies to many states (or an entire execution trace) of the system.

What’s invariant?

An invariant is a property that must hold in every reachable state of a system throughout its execution. It is a condition that remains unchanged, no matter which transitions occur.

In our water jug system, an example we used for a property is also an invariant:

This invariant guarantees that, regardless of the sequence of actions (filling, emptying, or pouring), the amount of water in the small jug will always be between 0 and 3 gallons, and the amount of water in the big jug will always be between 0 and 5 gallons.

Invariants are critical for ensuring that the system never reaches an invalid state, thus providing a global, unchanging constraint on the system’s behavior.

Covering unreachable states

Another invariant for our system is the statement that the states (1,1), (2,1), (1,2), (2,2), (1,3), (2,3), (1,4), (2,4) are not reachable.

This invariant ensures that whenever the small jug is partially filled (i.e., it has 1 or 2 gallons), the big jug must be either completely empty (0 gallons) or completely full (5 gallons).

It “covers” the unreachable states by ruling them out:

- If or , then the invariant requires or .

- Any state where and (for example, (1,1), (2,1), (1,2), (2,2), (1,3), (2,3), (1,4), (2,4)) would violate the invariant.

Because an invariant must hold for every reachable state, we’ll enforce that such states cannot be reached.

How can a property and invariant be a condition?

Wait a second—why do we say that a property or invariant can act as a condition? We defined a condition as a Boolean expression that serves as a guard for a state transition. So, where is the state transition that a property serves as a guard?

A correct way to think about it is to view a property as a mechanism that sets other state variables. Remember that you can always add more variables! For example, consider the invariant:

You can imagine this invariant as “setting” an additional state variable, say . When a state transition occurs, the invariant checks the new state and essentially assigns:

- if the invariant is satisfied, or

- if it is not.

In this sense, the property (or invariant) acts as a global condition on the system. Every time a state transition is attempted, the system “asks” whether the resulting state meets the invariant—i.e., whether is true. If not, that transition should not occur.

Thus, while a typical condition might directly check an input (like ), a property or invariant imposes a condition on the overall state space by effectively setting an extra variable. This perspective bridges the gap between guarding individual transitions and ensuring the system as a whole behaves correctly.

A Bonus: What’s an assertion?

Lastly, as a bonus, let’s define what an assertion is.

An assertion is a runtime check that verifies a specific condition—often a property or invariant—holds at a particular point in your program. Think of it as putting our theoretical rules into practice.

An assertion is a runtime check that verifies a specific condition.

Properties and invariants are global constraints on your system’s states. For instance, consider the invariant for our water jug problem:

This invariant is a rule that every valid state must satisfy. An assertion enforces this rule during execution. You might write an assertion like:

This assertion checks that the current state adheres to the invariant. If it doesn’t, the assertion fails, alerting you that something unexpected has occurred.

In short, while properties and invariants define what the system should always satisfy, assertions actively check these conditions at runtime—helping catch errors early and reinforcing the overall reliability and correctness of the system.

Comparing the terms

Now, let’s compare all the terms that we’ve defined:

| Term | Definition | Example in the Water Jug System | Role/Usage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | A Boolean expression (i.e. a predicate with free variables) that serves as a guard for a state transition. It determines whether an action is allowed in a given state. | Determines whether a specific transition (e.g., filling the small jug) should occur. | |

| Proposition | A declarative statement about a single state that is either true or false. It has no free variables once the state is fixed. | Asserts a fact about one state (e.g., in a given state, the big jug contains exactly 4 gallons). | |

| Predicate | A logical formula that may contain free variables and evaluates to true or false once the variables are instantiated. It becomes a proposition when all its variables are assigned. | Used to define conditions or properties that depend on state variables. | |

| Property | A predicate that expresses a constraint or rule expected to hold over a set of states or along an execution path. It is not confined to a single state but applies to many states in the system. | Describes global constraints (e.g., jug capacities) that guide the system’s behavior over many states. | |

| Invariant | A property that must hold in every reachable state of the system throughout its execution. It is a global, unchanging constraint that prevents the system from entering an invalid state. | Ensures the system never enters an invalid state (e.g., excludes states like (1,1) or (2,4) that violate the jugs’ physical limits). | |

| Assertion | A runtime check that verifies a particular condition (often a property or invariant) holds at a specific point in the execution. If the condition is false, the assertion fails. | Enforces that the system adheres to the stated condition at runtime, helping detect errors early if the condition (property or invariant) is violated. |

Conclusion

The Die Hard water jug problem isn’t just a cool puzzle—it offers a fun, hands-on way to understand essential testing concepts. By defining what a state is, what a sequence of states is, what an action is, and how a system can be represented as a formula, we laid the groundwork for precisely describing conditions, propositions, predicates, properties, and invariants. Along the way, we also introduced assertions as a runtime mechanism to verify that properties and invariants hold.

Grounding all of these terms in states and state transitions not only clarifies what they mean, but also shows how they ensure your system behaves correctly—from the moment an action is taken to the way its entire behavior unfolds over time. This understanding is critical for effective software testing; without a firm grasp of these concepts, testers risk missing key insights into how the systems they work with truly operate.

Until the next time – happy testing!