In Part 1, we built an autonomous system that beat all four levels of Super Mario Bros. without any human guidance. We treated the exploration as a mutation-based Genetic Algorithm, and it worked: the system discovered winning paths by exploring, replaying, and mutating input sequences. It found shortcuts, navigated complex enemy patterns, and even uncovered unexpected behaviors like the Level 4 collision bug. However, the exploration only validated one dimension of correctness: Mario’s progress. Our fitness function measured how far Mario advanced (x-position, level completion, and time), but the exploration couldn’t tell us whether the game actually behaved correctly. Did Mario’s velocity follow expected constraints? Were jumps causally justified? Did falling only occur when Mario lacked ground support? We had no way to know. This shows that autonomous testing by itself is not enough. To address this problem, we need a way to actually check state correctness. What we need is to plug in a behavior model!

Plugging the Behavior Model

We already had a behavior model from our earlier series (Part 1 and Part 2)—a model with causal, safety, and liveness properties that enforce game correctness frame-by-frame. The original model is available in the v2.0 branch:

1 | git clone --branch v2.0 --single-branch https://github.com/testflows/Examples.git && cd Examples/SuperMario |

This model is by no means complete and is limited to enforcing that Mario’s movement has a valid cause, that velocity never exceeds physical limits, that boundaries are respected, and that expected behaviors eventually occur. However, given that the model is composable, we will add two additional properties later.

The integration is simple. We pass the model to the same play() function that advances the game. Every frame, the play() method calls the model’s expect() method, which runs all the property checks. Here’s the implementation:

1 | def play(game, seconds=1, frames=None, model=None): |

Running autonomous exploration with the model

Now let’s see what happens when we run autonomous exploration with the model enabled:

1 | python3 tests/run.py --autonomous --play-seconds 300 --fps 300 --with-model |

Autonomous exploration with behavior model

The system explores thousands of states, validating every frame. Properties pass, pass, pass… until they don’t. Here’s what a failure from the video above looks like:

1 | 40s 432ms ⟥ [debug] ✓ Mario Mario's vertical velocity 0 is less than the maximum |

The model caught something. But here’s the catch: this failure could mean the game has a bug, or it could mean our model is wrong. We need to figure out which one.

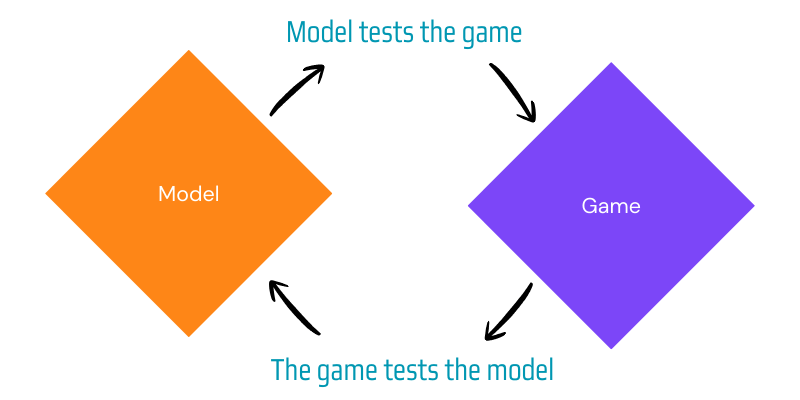

Bidirectional testing

When the model’s assertion fails, we face a fundamental question: Is the game wrong, or is the model wrong?

This is where bidirectional testing comes in. Unlike traditional testing where only the system is validated, for any non-trivial properties or transition relations, both the model and the game test each other simultaneously:

The model tests the game: Every frame, the model enforces that the game’s behavior satisfies the specified properties. If Mario moves right, there must be a cause (velocity or key press). If Mario falls, he must lack ground support. These are the model’s expectations.

The game tests the model: The game acts as the ground truth—it’s what actually runs and what players experience. When the model’s expectations fail, it reveals that the model’s understanding might be incomplete or incorrect.

This creates a self-correcting feedback loop:

Bidirectional testing

- If the game violates physics → game bug (model is correct)

- If the model’s expectations are wrong → model bug (game is correct)

Both components improve through their disagreements. Fix a game bug, and the model becomes more reliable. Fix a model bug, and game validation becomes more accurate. Each fix makes the other component more trustworthy.

Deciding if model or game has a bug

So how do we figure out which component has the bug? This is the classic test oracle problem—how do you know what the correct behavior should be?

The theoretical answer is sobering: deciding if a non-trivial model matches software is undecidable in general. For Turing-complete systems, there’s no algorithm that can always decide if the model and software agree for all possible inputs. Even for finite-state systems, you’d need to explore the entire state space, which is computationally infeasible for complex systems like our Mario game.

But here’s the practical insight: autonomous testing is just as good at finding when the model’s expectations don’t match the game as it is at finding when the game doesn’t match the model. We can’t prove the model is correct in absolute terms, but autonomous testing excels at finding disagreements. When a failure occurs, we just use a pragmatic approach:

- Analyze the failure: When a property fails, examine the saved path to understand what happened.

- Determine the cause: Is the game violating a physical law? Or is the model missing context about a valid game mechanic?

- Fix what’s wrong: Update either the game or the model based on the analysis.

- Re-run and validate: The bidirectional loop continues—both components get refined.

Deterministic execution

The game’s execution is fully deterministic, so the same sequence of inputs always produces the same state. This makes failure analysis much simpler. We record the full path that led to the model’s disagreement with the game’s behavior, and we can replay it exactly.

The value of deterministic execution can’t be overstated. Debugging weird corner cases found by autonomous exploration is already hard, but non-determinism and lack of reproducibility add significant complexity. With deterministic execution, we can replay the path as many times as we want and always hit the same failure. This makes failure analysis straightforward.

Deterministic execution also makes validating fixes much easier. When we fix the model, it doesn’t affect the game’s deterministic behavior, so we can verify the fix by replaying the failed path. Fixes to the game itself are a little bit trickier. We get the same benefit of re-running and validating the fix using the same failed path—as long as the game fix didn’t change the path behavior up to the point of failure. If the game’s behavior changed before that point, the failed path doesn’t lead to the same state, making the fix harder to verify.

The ability to save a failed path to a file was added in the v3.0 branch, which we’ll checkout and use it to see this process in action.

Updating the model

When we first ran autonomous exploration with the v2.0 model, failures started piling up. But here’s the thing: many of these failures weren’t game bugs—they were model bugs. The model’s expectations didn’t match the game’s actual behavior.

Most failures came from horizontal or vertical position adjustments. The game engine adjusts Mario’s position when he collides with bricks, shells, boundaries, and other objects. These adjustments are normal game behavior, but the v2.0 model didn’t account for them.

Let’s look at the original check_right_movement causal property:

1 | def check_right_movement(self, behavior): |

The moved_right() method returns true if actual movement is greater than 1 pixel (this also turned out to be a bug: we actually needed >= 1). When that happens, we assert that right movement has a valid cause by calling has_right_movement_cause, which returns true if the player has positive velocity or the right key was pressed.

This logic works in many game states, but it fails when Mario gets snapped by a collision. The game calls adjust_player_for_x_collisions() and adjust_player_for_y_collisions() in various code paths, causing position jumps that don’t reflect actual velocity. These adjustments can happen in the current frame or persist from the previous frame.

The fix was conceptually simple: skip the check when there’s a collision adjustment.

1 | if self.moved_right(actual_movement): |

But here’s the problem: implementing has_horizontal_collision_adjustment and had_horizontal_collision_adjustment turned out to be quite complex! A full reimplementation of that logic would blow up the model.

We needed ground truth from the game itself: direct information from the game engine about what actually happened, not our best guess. This meant expanding the game’s observability to expose collision information, viewport state, and other details the model needed. Given the fixes were needed in both the model and the game code, we created a v3.0 branch to implement them. We also added two new safety properties: check_does_not_overlap_with_solid_objects to ensure Mario never overlaps solid objects, and check_does_not_exceed_max_position_adjustment to enforce that per-frame displacement stays within physical limits.

1 | # If you already have v2.0 checked out, switch to v3.0 |

Expanding game’s observability

To give the model ground truth, we added observability directly to the game engine. The key addition is the CollisionInfo class that tracks when the engine adjusts Mario’s position due to collisions. The Player class now has a collision_info attribute with x_adjusted and y_adjusted flags that get reset each frame and set whenever the engine snaps Mario’s position. This information flows into BehaviorState so the model can access it directly.

We also added viewport tracking so the model can verify Mario stays on screen, and improved key state extraction to handle edge cases like simultaneous key presses. The model now has direct access to what the engine actually did, not what we tried to infer from deltas.

For complex behavior systems, instrumentation like this is absolutely necessary. Without it, the model would have to reimplement complex game logic just to detect when certain events occurred, which would blow up the model’s complexity and make it fragile. By instrumenting the game engine, we keep the model simple and focused on validating behavior rather than reverse-engineering internal state.

Finding and fixing more bugs in the model

Once we added and exposed collision adjustments, the check_right_movement and other checks became much more stable. It turned out that most of our checks needed to account for these adjustments.

Further runs, however, revealed more issues. For example, we had to update the model to use centerx for horizontal positions and rect.bottom for vertical positions instead of rect.x and rect.y, which change when sprite animations change size. This ensured that all velocity calculations were not affected by sprite animation changes, especially when Mario was in the big state after collecting a mushroom.

We also extended the history window from 3 frames to 4 frames (right_right_before, right_before, before, now) to better track multi-frame collision interactions, such as brick bumps that persist across multiple frames.

These changes fixed the model’s false positives. Collision snaps, brick bumps, shell kicks—all the edge cases that broke the v2.0 model—now worked correctly. However, finding and fixing bugs did not stop there, because once the model was updated and became much more stable, we were tempted to add a few more properties and started finding real game bugs.

Finding and fixing bugs in the game

The first bug we found was an instrumentation issue. The game was resetting collision_info before the recorder snapshot, so x_adjusted and y_adjusted flags read false even after teleport snaps. We fixed this by moving the reset into Player.update and propagating the flags through BehaviorState.

After that, we started to find real engine bugs. First, stacked brick collisions were snapping Mario to the wrong height because spritecollideany grabbed the first overlapping brick. We fixed this with a new get_vertical_collision method that collects all overlaps and chooses the correct ceiling or floor. We also found that gravity wasn’t being reinitialized after head bumps, causing anomalous velocity deltas. Additionally, we found issues with Mario disappearing. It turned out that the viewport could drift after position adjustments because the camera only advanced when velocity was nonzero.

But the most interesting bug was the Level 4 teleport. Autonomous exploration found a path where Mario would suddenly teleport across the screen near the firebar section. The model’s “Mario does not overlap any solid objects” property failed, but replaying the path showed something strange: Mario would brush against the firebar pedestal and then instantly appear far away.

Here is a video of the gameplay that we created using a saved failed path.

1 | python3 tests/run.py --autonomous --fps 300 --start-level 4 --load-paths --paths-file fails/4-1.json --play-best-path --save-video |

Level 4 teleport bug

Note how Mario teleports when hitting one of the firebar boxes!

Running the same failed path with the model enabled shows how our model detected this issue.

By the way, this is also a demonstration of how deterministic execution makes our lives easier!

1 | python3 tests/run.py --autonomous --with-model --fps 300 --start-level 4 --load-paths --paths-file fails/4-1.json --play-best-path --save-video |

1 | 11s 858ms ⟥ [debug] ✓ Mario Mario's horizontal move 6px is within max limits |

After analyzing the saved path, we discovered the root cause: two step colliders at x≈3580 overlapped by just 1 pixel. When Mario touched the firebar pedestal, the X collision resolver snapped him to the first collider, but he still overlapped the second collider. The Y resolver then interpreted this as a head bump and pushed Mario downward into the floor slab. On the next frame, the X resolver ejected him to the far edge of the slab, creating the apparent teleport.

Because this was a level layout bug, not an engine bug, we fixed it by removing the duplicate collider from the level map data and adding a 1-pixel offset guard to prevent future overlaps.

Conclusion

We started with autonomous exploration that could beat all four levels, but it only validated progress—not correctness. By integrating a behavior model, we transformed exploration into a correctness validation system that checked every frame.

The journey revealed the power of bidirectional testing: the model found game bugs, and the game revealed model bugs. This self-correcting feedback loop improved both components. We expanded the game’s observability to provide ground truth, fixed the model to use that ground truth, and then the fixed model found real game bugs.

The key insight here is that we don’t need perfect oracles. Instead, we need a behavior model composed of one or more properties that catch real bugs and a process that refines both the model and the game through their disagreements. Resolving these disagreements is enormously helped by deterministic execution, which makes this approach practical: we can replay failures as many times as we need, analyze them, fix what’s wrong, and verify the fix—most of the time using the same saved failed path.

The Level 4 teleport bug also revealed something important: the game’s collision resolution logic is not advanced enough to handle complex corner cases where Mario would be jammed between multiple solid objects or enemies. This means the model would still find these cases given enough run time.

Overall, autonomous exploration is excellent at traversing vast state spaces while behavior models ensure correctness throughout. Together, they find not just winning paths, but correctness bugs hiding in edge cases that most likely only your customers would find in production.